Last month marked the 210th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth. To the professional educator, Lincoln is endlessly fascinating. His family followed the frontier, and his accomplishments came in spite of the limited time he spent in a schoolhouse, among them some of the finest examples of political rhetoric in the English language.

So how did he do it, and what can we learn from his example? The present mantra in secondary education is “college and career readiness.” Lincoln invites an uncomfortable question: Had Lincoln attended a school on the vanguard of the college and career readiness movement, would it have prepared him for future greatness? Would Lincoln have become Lincoln?

This may seem like a strange question. After all, Lincoln is very distant from the present. But maybe that’s why he is helpful: His example stands far enough from the present to help us to see ourselves with fresh eyes.

When I look at Lincoln, three thoughts come to mind. Each challenges the sufficiency of the reigning paradigm for high school education.

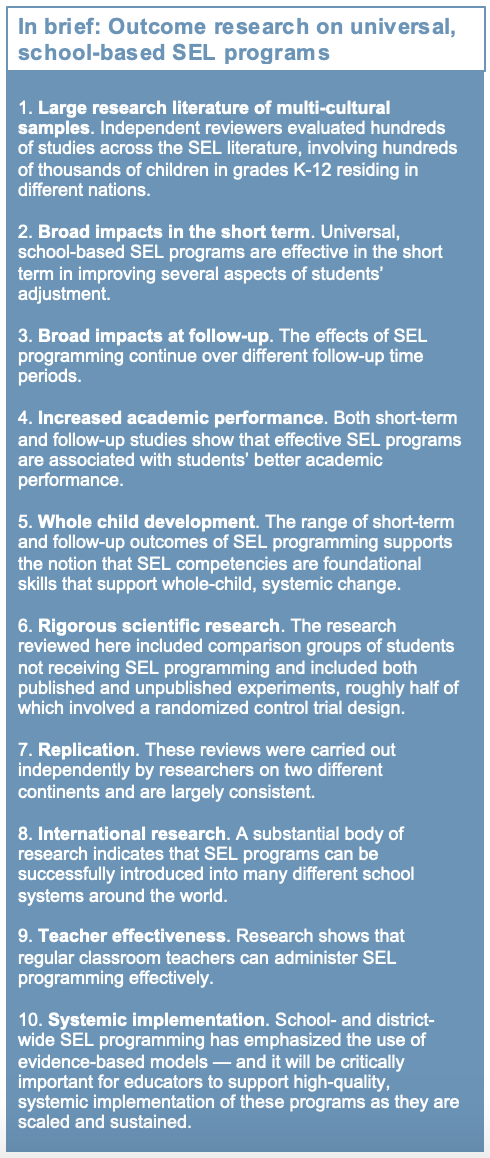

Perhaps we should pay more attention to culture-building. Much has been made of Lincoln’s self-education. We encounter stories of the young Lincoln walking miles to borrow a book and staying up to read by candlelight—a habit of self-improvement begun in youth and continued through adulthood. Historians tell us he studied grammar into his twenties and worked through Euclid’s “Elements” as a young congressman.

Lincoln’s selection of books is remarkable: Instead of “Captain Underpants” or “Twilight,” he read Aesop, Shakespeare, Plutarch, William Blackstone, and the Bible. Instead of test prep guides, he carefully studied schoolhouse textbooks in arithmetic and geometry. Instead of drafting a business plan and preparing a PowerPoint presentation, he studied collections of notable speeches and kept a copybook of poetry and learned lengthy passages by heart.

Sometimes missed is the fact that Lincoln was guided by a cultural consensus. There is a reason these authors could be found on the frontier. Lincoln was imitating rather than inventing an educational model—a model that was thought to be imminently practical for anyone ambitious to rise.

Lincoln’s examples invite examination: Would our culture (or imitation of our schools) have led Lincoln to read excellent books—cover to cover, as though they matter?

Perhaps we should pay more attention to communication. Today we seem more interested in the communication of machines than of human beings. Schools of Lincoln’s days sought to instill skill in the arts of language. Imitating the core of the schoolhouse education, he drilled himself in the rules of spelling, grammar, and logic. Instruction in the art of speaking and writing was grounded in imitation, so Lincoln read books on elocution and steeped himself in great literature.

Our college and career-oriented education focuses more on technology than eloquence—more on the medium than quality. It would be difficult to do more. Our high school students are hamstrung. They do not master grammar in earlier grades, so they are uncertain of correctness. Logic classes are virtually unknown. Students scarcely encounter poetry. Plutarch is unknown. Shakespeare is read in snippets and with difficulty, if at all. Yet Lincoln depended on his powers of communication. Much hung in the balance.

So Lincoln again invites self-examination: Would our schools have prepared Lincoln to give us the Gettysburg Address or Second Inaugural? Do they aspire to?

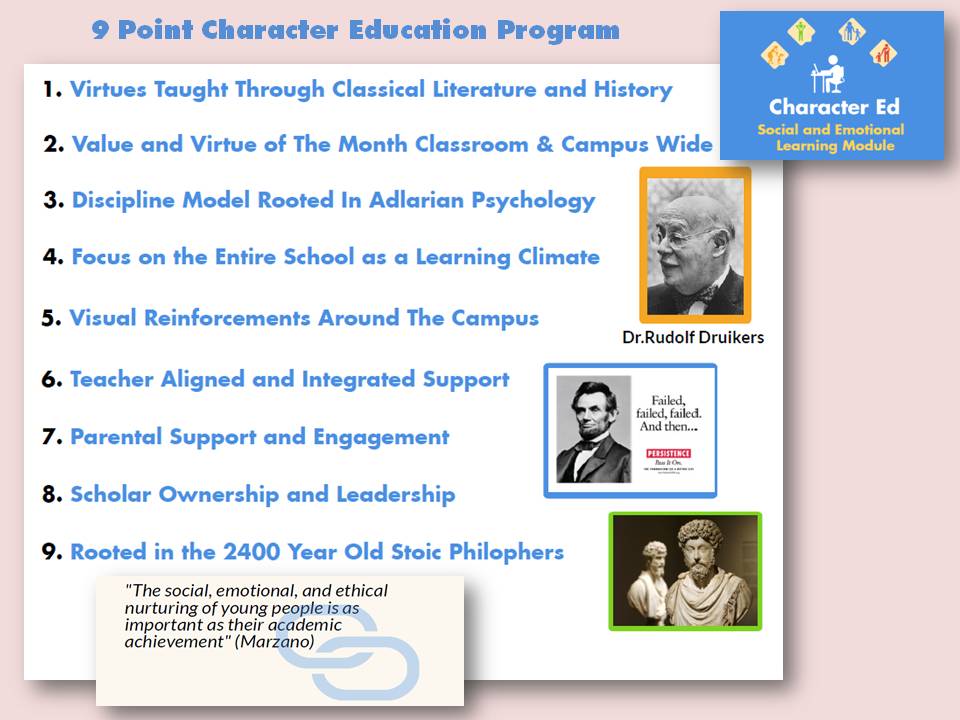

Perhaps we should focus more on character. Preparing for college or a career is well and good. But what is college for? What is the purpose of a career? In practice, college and career preparation means a focus on material gain—saving money by earning college credits in high school, preparing to earn money by practicing entry-level job skills.

This stands in sharp contrast to Lincoln. Following the lead of the schoolhouse, he gave himself an education intended to ennoble the heart with images of virtue and vice. His mind was full of fables and tales, and Shakespearean villains. His moral imagination was leavened by life experiences, such as his encounter with the slave markets of New Orleans. In short, Lincoln received exactly the education he needed if he was to sustain his resolve to seek justice as he shepherded the nation through the horrors of civil war.

Our contemporary notions of practical education have little regard for things that cannot be counted, so it has trouble teaching us what is worthy of our full energies. But those things that are not easily counted are exactly the sorts of things that defined Lincoln—wit and wisdom, humility and patience, eloquence and unbending humanity.

Lincoln modeled his self-education on the education of the schoolhouse. Maybe we should model our schoolhouses on his self-education.

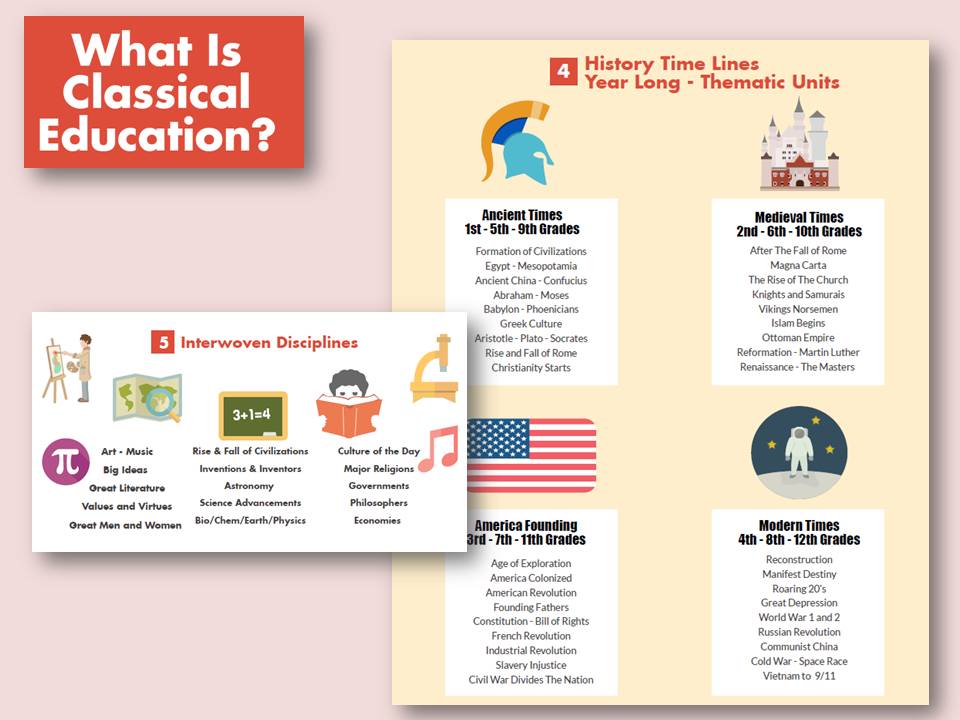

At the same time, while all four meta-analyses touched on these six domains, and while they reached similar conclusions overall, they also differed in one respect: Two of them focused on the short-term effects of SEL programs, synthesizing data (from 255 different research reports) collected shortly after students concluded a program (Durlak et al., 2011; Wiglesworth et al., 2016), and the other two focused on longer-term effects, using data (from 129 different reports) collected at various follow-up periods — Marcin Sklad and colleagues (2012) reviewed 75 studies, covering 2008 and earlier, that assessed outcomes at least seven months after the initial SEL program had ended, and Rebecca Taylor and colleagues (2017) reviewed studies conducted through 2014, with follow-up periods that varied from 56 to 195 weeks.

At the same time, while all four meta-analyses touched on these six domains, and while they reached similar conclusions overall, they also differed in one respect: Two of them focused on the short-term effects of SEL programs, synthesizing data (from 255 different research reports) collected shortly after students concluded a program (Durlak et al., 2011; Wiglesworth et al., 2016), and the other two focused on longer-term effects, using data (from 129 different reports) collected at various follow-up periods — Marcin Sklad and colleagues (2012) reviewed 75 studies, covering 2008 and earlier, that assessed outcomes at least seven months after the initial SEL program had ended, and Rebecca Taylor and colleagues (2017) reviewed studies conducted through 2014, with follow-up periods that varied from 56 to 195 weeks. Let’s set aside the debate about high stakes testing, the fact that schools and kids are more than their test results and focus on why Classical Education will naturally lead to improved outcomes in reading and comprehension. Here are the top 10 reasons our students achieve reading goals on tests AND are more prepared for future schooling and life;

Let’s set aside the debate about high stakes testing, the fact that schools and kids are more than their test results and focus on why Classical Education will naturally lead to improved outcomes in reading and comprehension. Here are the top 10 reasons our students achieve reading goals on tests AND are more prepared for future schooling and life;

In fact, cognitive scientists

In fact, cognitive scientists

Would our schools have prepared Abraham Lincoln to give us the Gettysburg Address or Second Inaugural? Do they aspire to?

Would our schools have prepared Abraham Lincoln to give us the Gettysburg Address or Second Inaugural? Do they aspire to?