Another year of declining test scores in America. Our Top 10 Ways We Create Readers.

Let’s set aside the debate about high stakes testing, the fact that schools and kids are more than their test results and focus on why Classical Education will naturally lead to improved outcomes in reading and comprehension. Here are the top 10 reasons our students achieve reading goals on tests AND are more prepared for future schooling and life;

Let’s set aside the debate about high stakes testing, the fact that schools and kids are more than their test results and focus on why Classical Education will naturally lead to improved outcomes in reading and comprehension. Here are the top 10 reasons our students achieve reading goals on tests AND are more prepared for future schooling and life;

ONE – Classical Education makes reading great works of literature CENTRAL to all we do.

-

-

-

- Our scholars are reading a lot, from novels to poems, plays, short stories, source documents, our kids are readers.

- Socratic discussions are paramount in a Classical School. Read aloud, a Charolette Mason addition to our Classical model, provides a chance to the entire class to listen, wrestle with rigorous texts and then do discuss what they’ve just heard. Reading then deep discussions helps make the text come alive.

- Teachers are interpreting the values and virtues of characters in novels exhibit and relating these ideas to the student’s world. Can you imagine the discussion around; ‘Was Robin Hood right in his actions?’

- Novel selections are at or above grade level. We set a high bar and help the students to achieve success.

- Vocabulary acquisition occurs from the weekly spelling tests AND from discovering new words in rich literature. Mix in Latin root words which will pop up year after year in the English and the sciences and students learn in a multi-pronged approach.

-

-

TWO – Reading stories full of adventure and drama and real human emotions are interesting. They bring students into the characters and ideas happening in the book. The focus on informational text is important but there is so much more to reading! Many national reading programs, especially in the early grades, are short stories and text choices that don’t make sense to the students. By picking thematic texts and using entire books (many of which are recognized classics), the students get a deeper richer enjoyment out of what they are reading. For example, reading Elie Wiesel’s Night, during the Holocaust history unit, puts human emotion and context into both history and English lessons.

THREE – Informational text, where most States have moved their reading standards are important, but within balance to non-fiction. Informational text analysis happens in English AND History, Science and the Art. Where many schools focus on informational text in English class, in a Classical school, students dissect source documents from history, new articles that could be hundreds of years old, and add on the informational text that compliments classical novels. The balanced blend of fiction and non-fiction is important to student engagement and context.

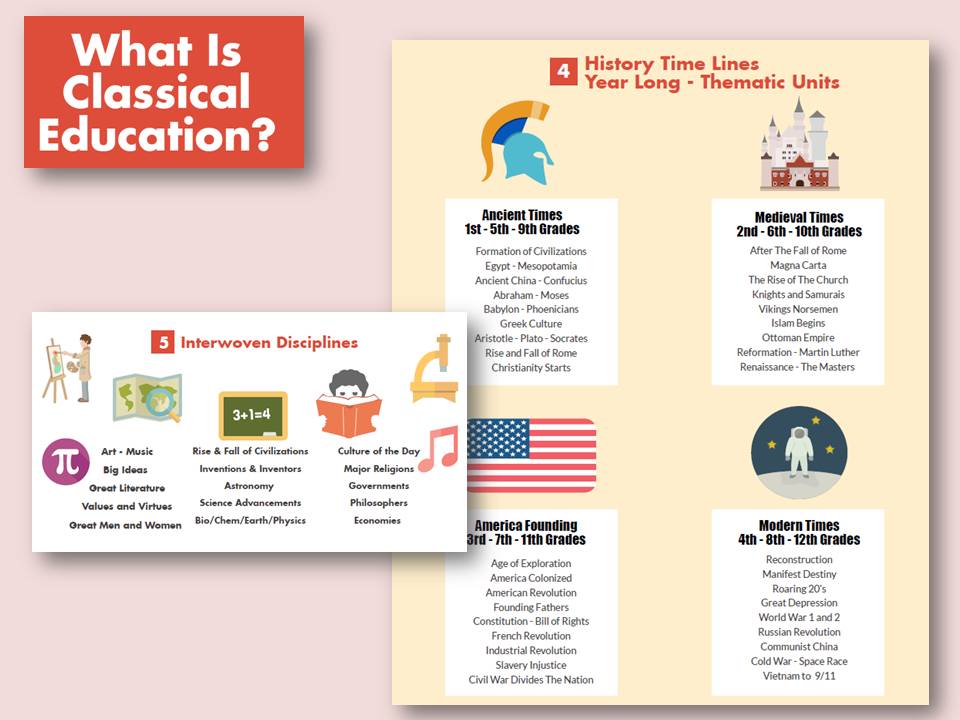

FOUR – Interwoven subjects make sense to the students. When the scholar reads Johnny Truman, a classical novel about a boy that is set in Boston prior to and during the outbreak of the American Revolution. The novel is ideal for teen-aged readers. With themes include apprenticeship, courtship, sacrifice, human rights, and the growing tension between Patriots and Loyalists as conflict nears. Events depicted in the novel include the Boston Tea Party, the British blockade of the Port of Boston, the midnight ride of Paul Revere, and the Battles of Lexington and Concord. The impact of Classical Education found in Ethos Logos schools is that as the novel is being interpreted, in history, the students are learning the facts and stories that lead up to the American revolution. In art class, they are learning how artists interpreted the birth of America and in the music, they are listening to the patriotic-themed songs of the late 1700s. This emersion into the time period is year-long and makes sense to the students. More on Thematic or Interwoven Instruction.

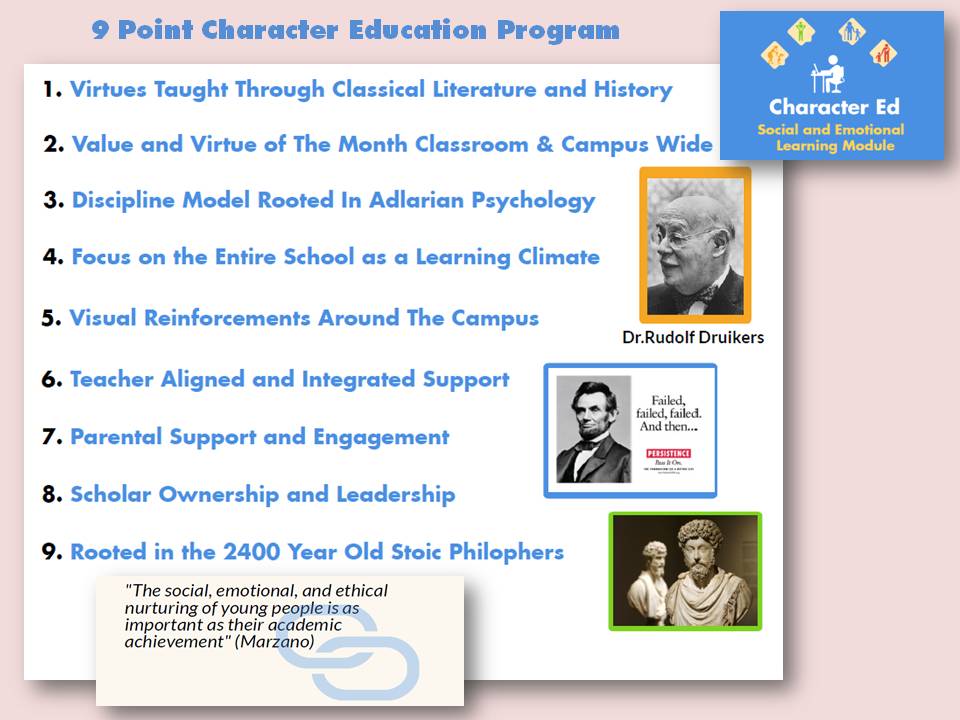

FIVE – Value and Virtue themes are not an afterthought but a focal point. Each month, we focus on school-wide values and virtues that open a door for teachers to discuss in the classroom. We have provided hundreds of lesson prompts to assist teachers in getting to the core values we are covering in the class, in the hallways, and on the playing fields. Check out Pilar 1 and 2 in the Ethos Logos Character Module.

SIX – Classical Education schools WRITE and WRITE and WRITE. The hallmark of a Classical school is high-frequency writing. From opinions to narratives on the novels being studied to journals in history or science. Our scholars are READING, INTERPRETING and WRITING across subjects.

SEVEN – Whole Word AND Phonemic Awareness in the early grades. (more HERE) The debate between whole word instruction and phonetics in the early grades has been going on in America for years. We supplement our curriculum offerings to Kinder, 1st and if needed 2nd grade with a phonetic program that gives teachers the tools needed to address all their student’s needs. Beyond the curriculum, we have a detailed assessment system that identifies struggling readers and brings in interventions to support their early love of reading.

EIGHT – Cultural References – Education is the passing down of knowledge from one generation to another. The collective knowledge passed down is built upon the great thinkers of their time, borrowing, building and retuning the ideas of those thinkers of the past. From Aristotle to St. Augustine, from Adam Smith to Milton Freidman’s philosophies around economics, human nature and sciences have evolved from generation to generation. Having a wide knowledge base on the arts, literature, history, and sciences help Classical Education scholars comprehend texts with a wider range and depth.

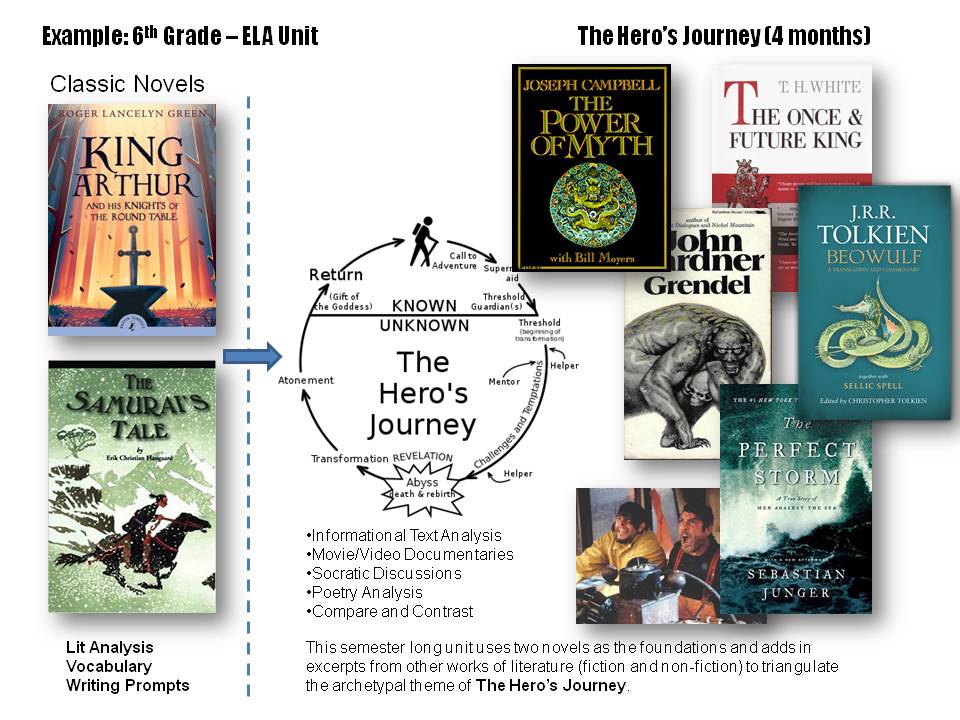

NINE – Triangulation and Interpretation as full English units. Our English units are built out to dissect, interpret, write about and discuss the novel of the month but also we add in historic source documents, short stories, fiction, and non-fiction themed stories and poetry to help the teacher to triangulate instruction between multiple sources. Check out a sample of unit on The Heros Journey tied to the novels King Arthur and Samuari Tale.

TEN – Teachers that are supported on WHAT to cover in the classroom so they can focus on HOW and WHY the content is important to the students. I was amazed to learn that a number of school districts in America provide the required list of standards and tell the teacher to go find content to teach the standards. Our schools have layer upon layer of curriculum and add on resources to support the teachers in their lesson planning. We have built out units with daily lessons and a full buffet of resources organized by major categories for the teacher to pull from and customize to meet their interests and their unique classroom make up. Check out our SPRITE History program to get a sense of how this works in a school.

BONUS – ELEVEN – Social and Emotional Learning Improves Student Outcomes – HERE

To Reverse The Decline In Reading Scores, We Need To Build Knowledge

Scores on standardized tests given across the country have declined, and the gap between high- and low-achievers has widened. There’s plenty of hand-wringing, but commentators continue to overlook an obvious explanation: we’re not giving vulnerable students access to the kind of knowledge that could help them succeed.

It’s become a predictable biennial ritual. Reading and math scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress—also known as “The Nation’s Report Card”—are released amid great fanfare. A few states and districts are singled out for commendation, but the overall picture is bleak: stagnant or declining scores, especially among the lowest-achieving students.

This year’s scores, released on October 30, are scary enough to qualify for Halloween. The tests revealed mixed results in math and an even grimmer picture than usual in reading. Among 4th graders, reading scores have declined in 17 states since the last test administration in 2017. And in 8th grade, scores declined in a whopping 31 states. All demographic groups of 8th graders lost ground except Asians, but those at the bottom lost more: the top scorers declined by one point, and the lowest declined by six points.

It can be dangerous to draw conclusions on the basis of NAEP data. But the consistently bad news about reading scores—which have been stagnant since 1998—is a pretty clear indication we’re doing something wrong. Indeed, the last time NAEP scores were released, in April 2018, the board that administers the tests convened a panel of experts to discuss the lack of progress in reading. The consensus was that we’ve been teaching reading comprehension in a way that doesn’t correspond to scientific evidence.

The experts explained that the vast majority of American schools approach reading comprehension as though it were a set of generally applicable skills, like “finding the main idea” and “making inferences”—the skills the tests appear to measure. Especially in schools where test scores are low, students practice these “skills” for hours every week on books on a random variety of topics that are easy enough for them to read independently. The theory is that it’s more important for children to acquire comprehension skills than substantive knowledge, because they can use the skills to acquire knowledge from reading complex texts later on–and to understand the passages on standardized tests at the end of the year.

In fact, cognitive scientists have found that the most important factor in comprehension is how much background knowledge readers have relating to the topic: the more you have, the easier it is to understand a text and retain the information. So if schools want to boost reading comprehension, especially for students who are unlikely to pick up academic knowledge and vocabulary at home, the key is to expand knowledge through a curriculum that includes lots of history, science, and the arts—the very subjects that are being marginalized to make room for more practice in comprehension “skills.” The reason many students score poorly on tests is not that they haven’t learned the skills; it’s that they can’t understand the reading passages in the first place.

In fact, cognitive scientists have found that the most important factor in comprehension is how much background knowledge readers have relating to the topic: the more you have, the easier it is to understand a text and retain the information. So if schools want to boost reading comprehension, especially for students who are unlikely to pick up academic knowledge and vocabulary at home, the key is to expand knowledge through a curriculum that includes lots of history, science, and the arts—the very subjects that are being marginalized to make room for more practice in comprehension “skills.” The reason many students score poorly on tests is not that they haven’t learned the skills; it’s that they can’t understand the reading passages in the first place.

It appears NAEP administrators have short memories. At this year’s event, there was no mention of the analysis offered by the experts on last year’s panel. When an audience member asked about the discrepancy between math and reading scores, the NAEP official taking questions merely shrugged. “We don’t seem to know how to move the scores for reading but we do for math,” was all she offered—along with an aside about how the “Reading Wars” seem to be back.

That’s a reference to a debate that erupted in the 1990s about the best way to teach children how to sound out words. Thanks to reporting by radio journalist Emily Hanford, it’s recently become clear that many children still aren’t being taught phonics in the systematic way that is backed by abundant scientific evidence. That news seems to have also reached Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, who spoke at the “NAEP Day” event. In addition to touting school choice as the remedy for low reading scores, DeVos blamed them on teachers, declaring that “America’s educators know what it takes to teach a student to read”—meaning phonics. In fact, that’s the problem: many educators don’t know, due to deficiencies in their training. Nor have they been informed about the need to build knowledge to boost comprehension—which is perhaps an even more widespread problem, and certainly one that has been more overlooked.

This year’s NAEP Day panel, composed of educators and state education officials, also failed to mention the elephant in the room identified by the panel last year. Although the topic was educational equity, no one brought up the difference in access to knowledge between kids from wealthier, more educated families and their less privileged peers—or the fact that schools are failing to build knowledge for the children who need it most. Instead, the panelists urged the usual recommendations: the need to have high expectations for all students, the importance of basing interventions on data.

Those exhortations sound good. But if teachers don’t provide students with the information they need to meet high expectations, and if the data they rely on leads only to a doubling down on the comprehension “skills” it purports to measure—as is usually the case–reading scores will stay low and the gap between students at the top and bottom will persist. School choice won’t help either, unless there are more choices that include knowledge-building curricula and an easier way to identify them. And while the pundits and officials continue to overlook a root cause of the problem, untold numbers of students will continue to suffer.

Natalie Wexler is the author of The Knowledge Gap: The Hidden Cause of America’s Broken Education System—and How to Fix It (Avery, 2019). She is also the co-author, with Judith C. Hochman, of The Writing Revolution: A Guide to Advancing Thinking Through Writing in All Subjects and Grades” (Jossey-Bass, 2017). Her articles and essays have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and other publications.