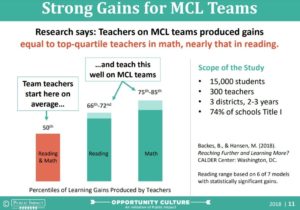

Check out the OpportunityCulture.org program which allows strong teachers to stay in the classroom where they can use their skills to impact scholars AND to help other teachers perfect their craft.

The Master Teacher concept is not new but the Opportunity Culture framework has formalized the process and given us the research-backed answers on how to implement a program well.

Learning to Lead as a Multi-Classroom Leader

By Hadley Moore, March 4, 2019; published by EducationNC, April 3, 2019

In 2015–16, I was a high school English teacher at an elite, private college-prep high school. In 2017-18, I became an assistant principal at an inner-city elementary school. How on earth did that happen?

I loved being a high school English teacher. It was my dream job, molding and shaping young people’s lives through literary works that made my heart sing. I could have quite happily remained ensconced in my classroom for life. However, I was feeling restless, and candidly, a little bored. I wanted more—I wanted a greater impact, and I wanted the opportunity to network with other educators.

Enter the chance to become an Opportunity Culture multi-classroom leader, or MCL. I left my safe classroom in that smoothly oiled prep school to lead a team of six teachers, overseeing six classrooms and four courses in an urban public high school in its first year of using Opportunity Culture staffing models. On the first day, when I couldn’t figure out where to find printer paper in that vast, impersonal new building, I cried.

Despite the culture shock, I threw myself into my MCL and coaching role, and I couldn’t be more grateful for that experience. I would not be the school leader or competent instructional coach that I now must be on a daily basis if not for the foundation of Opportunity Culture. It was a true “opportunity” to grow, and it has led me in a professional direction I never could have imagined.

The MCL role allowed me to grow and feel confident as an instructional leader. Without this experience, I would not have pursued administration. When I became the assistant principal at Washington Irving Elementary School in the Indianapolis Public Schools, I put my MCL skills to work:

Building relationships: This is key to any successful school climate and culture. What I loved about being an MCL was that we were embedded coaches and not evaluators. My team and I worked side by side to plan and deliver great instruction. Alongside them I co-taught, introduced the curriculum, charted and analyzed data—and I observed both the mundane and the fantastic. As a result, I could build encouraging and supportive relationships with the teachers who were under my umbrella. I was not a threat or an authority figure; I was a partner. Their success was my success. Their failures were my failures.

Now, I can see how much the MCL role helped me build relationships and have fun doing it! Once I got into an evaluator position, I missed the comfort that was easier to establish in my MCL role. However, it was just as important, if not more so, to work at building relationships with my teachers as an assistant principal. I wanted them to see me as their coach, their cheerleader, and their teammate, just as my teachers did when I was an MCL.

Focusing on rigor: The MCL role made it clear that instructional rigor motivates and engages students. Our kids want to be challenged; they want to be respected enough to be entrusted with lessons, assessments, and performance tasks that allow them to demonstrate the fullness of their talents and abilities. The most successful and impactful teachers were the ones who understood that and incorporated rigor every single day. From my prep school work, I brought content knowledge, high expectations, and enthusiasm for reworking a lackluster curriculum and book list. We replaced tired, whitewashed young-adult texts with meaningful multicultural literature written for adults. The kids thrived, and their teachers blossomed as well—elated and empowered with the growth they saw in students’ reading, writing, and conversations in their classrooms daily.

Collaborating: At first, the teachers I supported were a bit suspicious, since my role had never existed before. What was I there to do? How was I going to improve their practice—or would I just place more demands on their already limited time? I had to establish a collaborative team culture in the English department, and that started with me. Our weekly meeting was sacred, and we all showed up on time ready to interact. I modeled that, but they perpetuated it. My office became the hub of the department—and not just because of the sodas and candy I kept stocked. We shared our challenges and our successes with one another—daily, beyond our formal weekly meeting. We observed one another’s lessons, offered opinions on curriculum changes, and chose texts in tandem. Our conversations that were once on the surface level of “how was your weekend?” naturally morphed into “what was the impact of this morning’s Maya Angelou text on your classroom discussion?” Ultimately, it was the commitment to our shared students—and our emphasis on instructional excellence—that allowed us to build the collaborative culture that ensured our success.

I would not have had the courage, curiosity, and relationship-building skills to take on an assistant principal position—let alone in an elementary school!—were it not for the experiences I had building a team and transforming an academic culture as a high school English MCL. I am grateful daily for Opportunity Culture and my own opportunity to grow and develop myself alongside those beloved, respected, hardworking teachers.

Hadley Moore was the assistant principal of Washington Irving Elementary School in Indianapolis Public Schools, and an Opportunity Culture Fellow in 2017–18. Read more columns written by Opportunity Culture educators, many with accompanying videos, here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.